Cascadia, like its borders, has an imprecise history.

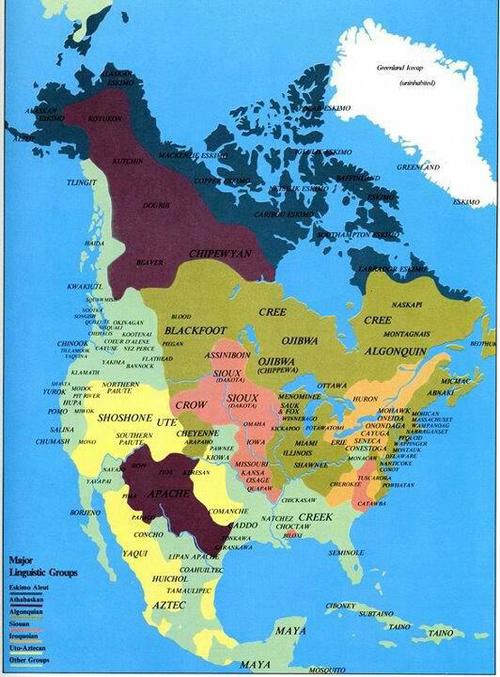

The idea of an autonomous state along the Pacific coast dates back hundreds of years to when the area was first being explored. It was originally envisioned by Thomas Jefferson after he sent Lewis and Clark into the Pacific Northwest in 1803. When Lewis and Clark first arrived, they found a densely populated and diverse region. Before 1800, it is estimated that more than 500,000 people lived within the region in dozens of tribes such as the Chinook, Haida, Nootka and Tlingit.

Jefferson foresaw the establishment of an independent nation in the Western portion of the North American continent that he dubbed the “Republic of the Pacific”. In his mind, this nation was to be home to a “great, free and independent empire”, populated by American settlers, but separate from the United States politically and economically, and eventually becoming a great trading partner exploring its own democratic experiment. In an 1813 letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Jacob Astor he congratulated Astor on the establishment of Fort Astoria (the coastal fur trade post of Astor’s Pacific Fur Company) and described Fort Astoria as “the germ of a great, free, and independent empire on that side of our continent, and that liberty and self-government spreading from that as well as from this side, will insure their complete establishment over the whole.”

It was during these early years of exploration that the root of term Cascadia first came into being. It is credited to Scottish naturalist David Douglas, after whom the Doug Fir was named, and who explored the region in depth throughout the 1820’s. While he was searching for plants near the mouth of the Columbia gorge in 1825 he was struck by the areas ‘cascading waterfalls’. As he writes in his journals he talks in depth about the mountains by these ‘great cascades’ or later, just simply the Cascades, the first written reference to the mountain range that would later bear this name.

Surrounding these mountains lived a hardy and independent people. Even before the area was unified as the Oregon Territory, the idea of an autonomous state was embraced by those who had recently moved to the region.

John McLoughlin, the chief factor of the Columbia District, administered from Fort Vancouver and which included Oregon, Washington and large swaths of British Columbia, was involved with the debate over the future of the Oregon Country. As a member of the Oregon Lyceum, a forum and literary club for influential pioneers, and the first organization to publish a newspaper west of the Rockies, he was engaged at the forefront of a political debate to decide wether or not to form an independent government.

At the time neither the United States nor Great Britain could claim the Oregon Country under the terms of the Treaty of 1818 signed at the conclusion of the War of 1812. During these debates in Oregon City the European settlers argued about whether an independent country or a provisional government should be formed. Beginning in the fall and winter of 1840-1841 before British claims north of the Columbia River were ceded to the U.S.A. by the Oregon Treaty of 1846; Chief Factor John McLoughlin advocated for an independent nation.

Those lyceum members advocating an independent country were mainly British, including Dr. McLoughlin and his HBC employees, although many former fur trappers, predominately French Canadian, Roman Catholics, and the region’s Jesuit missionaries sided with McLoughlin on this issue. His view won support at first and a resolution was adopted, but was later moved away from in favor of a resolution by George Abernethy of the Methodist Mission to delay the formation an independent government to see if the United States would extend its jurisdiction.

In the February edition of the Oregonian and Indian Advocate, a case was laid out by the articles author, known only as ‘W’, for the logical creation of a country along the Pacific Coast, stretching from California through the entirety of the Oregon Territory, then comprising Oregon, Washington, Idaho and British Columbia. At this time, the Oregon country was a neutrally aligned area in which the British, American, Russian governments all had a stake, with Spain still controlling large swaths of California.

In the article, the author argues that the general prevailing sentiment of the US populace was the country was large enough, noting that “The feeling is now very prevalent that we have territory enough. It is in every one’s mouth, ‘We have territory enough, why do we want more?” and it would be hard indeed to persuade the people to relish a war for a tract of land most of them do not want, and many of them would be unwilling to have attached to the United States. With the merchants, and the people against it, shall we have war for Oregon? Will the Executive, will the Congress plunge the nation in carnage and blood against the people’s will, for a tract of country the nation cares but little for?

He goes on to argue that “during this time, while the United States and England are with the greatest ceremony disputing and negotiating, thousands will be pressing into the territy. It will be settled, and Oregon and California will be united in a common cause and destiny. Then will come the realization of the event which Mr. Jefferson predicted, and “the whole extent of that coast will be covered with free and independent Americans, unconnected with us, but by the ties of blood and friendship.”

He even argued the important role that bioregionalism would play “Nature herself has marked out Western America for the home of an independent nation. The Rocky Mountains will be to Oregon, what the Alps have been to Italy, or the Pyrenees to Spain. The Nation which extends itself across them, must be broken in the centre by the weight of the extremities. When we merely glance at a map, it seems absurd to suppose that Oregon is to belong to a nation whose capital is on the Atlantic Seabord. What! Must the people of that land be six months journey from the seat of Government? Must they send their delegates four thousand miles to represent them in the legislature of a nation with whom they can have but few common interests or sympathies?”

Military Commander Charles Wilkes, leader of a 1841 expedition to map the Pacific Northwest was the first to fully document what later became known as the Cascadia bioregion. His map, published in 1845 fully documents the interconnectedness of the then Oregon Territories. The illustration cuts off in the north due to Imperial Russian control, and in the south due to Imperial Spanish control.